Meeting Grandma

Grandma became a person in her 85th year. Before then, I didn’t doubt that she was human, after all, I had seen her do that most human of things— poop!— many times, the consequence of living in a house where the bathroom doubled as a corridor between two rooms. But I didn’t think she was a person. She was Grandma. The one who always had Grandpa’s wheat sandwiches neatly packed into a cooler with a brown lid, who called me “Gogoro eyo” each time she saw me, as though she was newly surprised by my height. The one who had quiet conversations with Uncle Timi and Grandpa, other non-persons, about troublesome cousins. Even though I had heard her laughter, which was so soft that I imagined that it was muffled by an invisible wall of pillows when it came out of her, it had never occurred to me that she could crack a joke. And though I knew that Mommy Hospital Road, Mommy Benin and Mommy Ariyo were her sisters, it didn’t occur to me that she knew sisterhood in the same way that I did— the sharing of clothes and jewelry, (or as my older sister, Funto, would likely say, “the taking of clothes and jewelry without permission), the matching outfits at family parties, the frequent teasing. Though I had eaten gratefully from the pot of stew that she brought for Funto, and our brother, and me, the time we ran low on food and money when Mommy travelled, it did not occur to me that she had made it out of anything other than her grandmotherly duty, out of her love. Because she was not a person, and only persons could love.

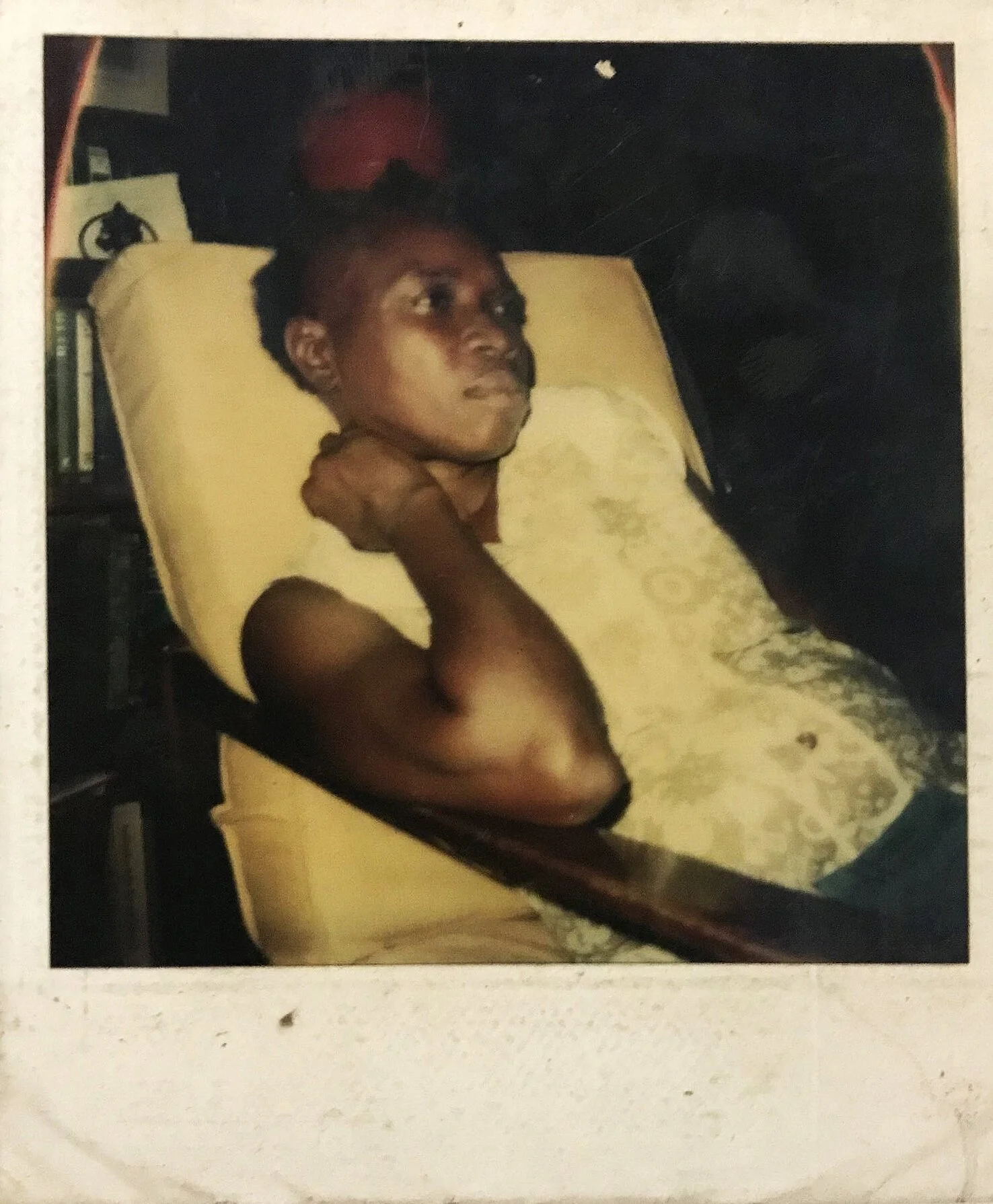

Is this who I missed? A casual photo of Grandma that I found after she died.

But in the last week of her 85th year, things started to change. I had gone home from school on the weekend to find Mommy and Funto planning to surprise her on her birthday. Funto, in particular, had ordered a strawberry ice-cream cake of her own volition, because, even though we grew up in the same house, and saw Grandma with the same frequency, she somehow recognized that Grandma was a person, and wanted her to feel loved. On her birthday, I got in the car with Mommy and Funto, still slightly confused, but also eager to meet Grandma the person. During our visit, I caught a glimpse of her when she willingly stopped in the doorway to let Funto photograph her, her face beaming with the unexpected joy that Funto and Mommy had hoped their planning would elicit. When a month or so later, Mommy suggested that I interview her for a presentation in my developmental psychology class, I thought to myself, “more opportunity to meet this person who has been here all along!” But she became a little ill so I had to go without the interview. Soon after, she became too weak to stay at home, so Uncle Timi admitted her at his hospital, and Grandpa came to stay with my family.

When I went home again one weekend, Mommy and Funto talked about how bored Grandma was at the hospital, so I bought her a copy of Chicken Soup for The Soul, because I had gotten into reading the series, and I thought she might like it too. A week or so later, I visited home in the middle of the week, so I went to the hospital with Mommy. I asked Grandma if she liked the book, the first time I ever asked her if she liked anything, because I was starting to see that she was a person who could like and dislike things. But she said the title confused her. Was this a book of chicken soup recipes? I laughed and said, no, that it was a book of short stories about different people’s lives, arranged according to themes. She said, oh okay, because she had been confused as to why I would give her a cookbook to read in the hospital. She laughed when she said this, and I laughed too, one of the few times, I think, that we laughed together. She started to feel a little better, but not well enough to return to running a household, so she joined Grandpa and my family at our house. And it was as if the fact that I had started to recognize that she was a person loosened a dormant love for her in me, because I started going to class from home so that I could help to care for her. But I had never really had to care for anyone in my life, so my support was limited to small things— helping Grandma dial phone numbers, bringing things to her, and, one time, rubbing pain-relieving gel into her aching back.

A few weeks passed and because Grandma was getting better, there was talk of her and Grandpa going home so they could settle back into their life. Then one day, when Kayode’s mommy, Funto’s future mother-in-law, came to visit, Grandma said her head hurt. Kayode’s mommy went and sat with her, trying to help her get as comfortable as possible and I kept my distance, because even though love was awoken in me, my care-taking skills were still non-existent. Around 5pm, Kayode’s Mommy came out of the room with Grandma propped up against her. She said that Grandma wasn’t talking, and I became worried and called Mommy. Mommy was home in 20 minutes. Uncle Timi came about 100 minutes after her. He checked Grandma’s blood pressure. It was normal. He asked her what she wanted to eat and it took a moment, but she said eba. So I went upstairs to my friend, Bie’s house to tell her mom, who had come to visit and seen the worry that lined Mommy’s face, and Kayode’s mom’s, and Grandpa’s, and mine, that all was well. Grandma was going to eat her eba with soup and be just fine. But the next morning, we had to carry Grandma to the bathroom, because she couldn’t wake up to pee. I remember seeing the limpness in her arms and her legs, but being unable to stay to help because I had to go to school. The next week or so was a blur— Grandma’s blood pressure was 300 over something when she got to the Teaching Hospital. It took a while but because Mommy worked there, she got a bed at the spillover ward in the Emergency department. My older cousin, Auntie Tayo, and Grandma’s sister, Mommy Hospital Road, came to join the troops. We all took turns sitting at Grandma's bedside, waiting for her to wake up from the coma she was in. Auntie Fehintola was coming from America too, and I was sure, absolutely certain, that when she did, Grandma would hear her voice, and say “ah, omo mi ti de o,” and open her eyes to see her beloved child. When the doctors came on ward rounds, and slapped Grandma’s chest so hard that I was sure that it echoed into the hallway, when they shouted “Mama, Mama, Mama!!” with their mouths right next to her ears, I wanted to tell them to stop. Couldn’t they see that they were hurting her? I was not worried by how still her body remained despite the force that was hitting it.

On the day that she died, I hadn’t slept much because I had worked late on a paper, so when Auntie Tayo walked in to the living room and said “Mama ti lo o,” I was lying on the couch halfway between sleep and wakefulness. But I did not doubt what I heard because I opened my eyes to see Mommy Hospital Road throw her 83-year-old body back on the chair, and start to cry. Me? I threw my legs to the floor and said “Ehn?? It’s a lie!” Because even though Mommy had been going about the world like a zombie, her face thick with worry, because she knew that Grandma’s body had been shutting down since the day she fell into the coma, I had not noticed, because I didn’t want to notice, because I was sure that Grandma would live.